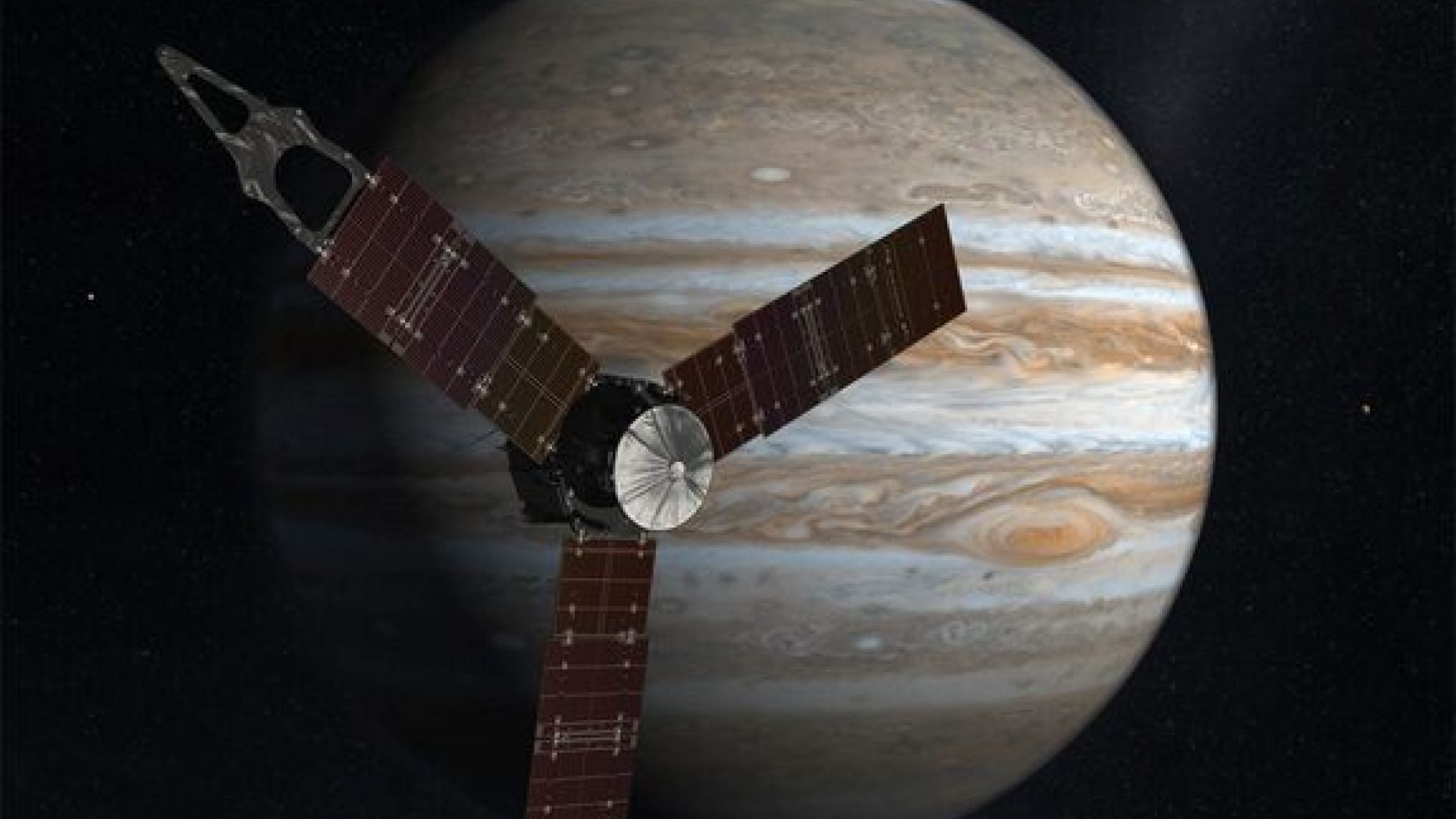

Jupiter-Bound Probe Changes Orbit in Deep Space

NASA’s Jupiter-bound Juno probe fired its main engine Thursday (Aug. 30) to help set up a speed-boosting flyby of Earth next year.

The engine burn — which took place when the Juno spacecraft was about 300 million miles (483 million kilometers) from Earth — began at 6:57 p.m. EDT (2257 GMT) Thursday and lasted nearly 30 minutes. It appears to have worked according to plan, changing the probe’s velocity by about 770 mph (1,240 kph), researchers said.

“This first and successful main engine burn is the payoff for a lot of hard work and planning by the operations team,” Juno project manager Rick Nybakken, of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement.

“We started detailed preparations for this maneuver earlier this year, and over the last five months we’ve been characterizing and configuring the spacecraft, primarily in the propulsion and thermal systems,” he added. [Video: A Look at Juno’s Mission]

After another burn this Tuesday (Sept. 4), Juno should be on course for its Earth flyby on Oct. 9, 2013, which will bring the probe within 310 miles (500 km) of our planet. Earth’s gravity will give the spacecraft a big push, boosting its velocity by 16,330 mph (26,280 kph) and placing Juno on its final path to Jupiter, researchers said.

Juno, which launched on Aug. 5, 2011, is slated to arrive at the solar system’s largest planet on July 4, 2016.

Once there, Juno will orbit Jupiter 33 times from pole to pole, using its eight science instruments to peer beneath the gas giant’s thick clouds. (The spacecraft takes its name from the goddess Juno, who was able to see through the clouds devised by her husband Jupiter in an attempt to hide his mischief.)

The main goal of the $1.1 billion mission is to learn about Jupiter’s atmosphere, magnetosphere, composition and origins, and to determine if the planet has a solid core, researchers said.

“We need to go to Jupiter to learn our history because Jupiter is the largest of the planets, and it formed by grabbing most of the material left over from the sun’s formation,” said Juno principal investigator Scott Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “Earth and the other planets are really made from the leftovers of the leftovers, so if we want to learn about the history of the elements that made Earth and life, we need to first understand what happened when Jupiter formed.”

Juno will put another 1.4 billion miles (2.25 billion km) on its odometer by the time it reaches Jupiter, Bolton said. The probe is making its long journey powered by the sun — the first time a solar-powered craft has ever traveled as far out as Jupiter.

The 8,000-pound (3,267 kg) spacecraft boasts three different solar arrays, each as big as a tractor-trailer. The arrays’ 18,698 solar cells will generate about 400 watts of power out at Jupiter — the equivalent of four 100-watt light bulbs.

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts