Why Is The Moon’s Crust Composed Of Just One Mineral? Researchers Shed Light On Mystery

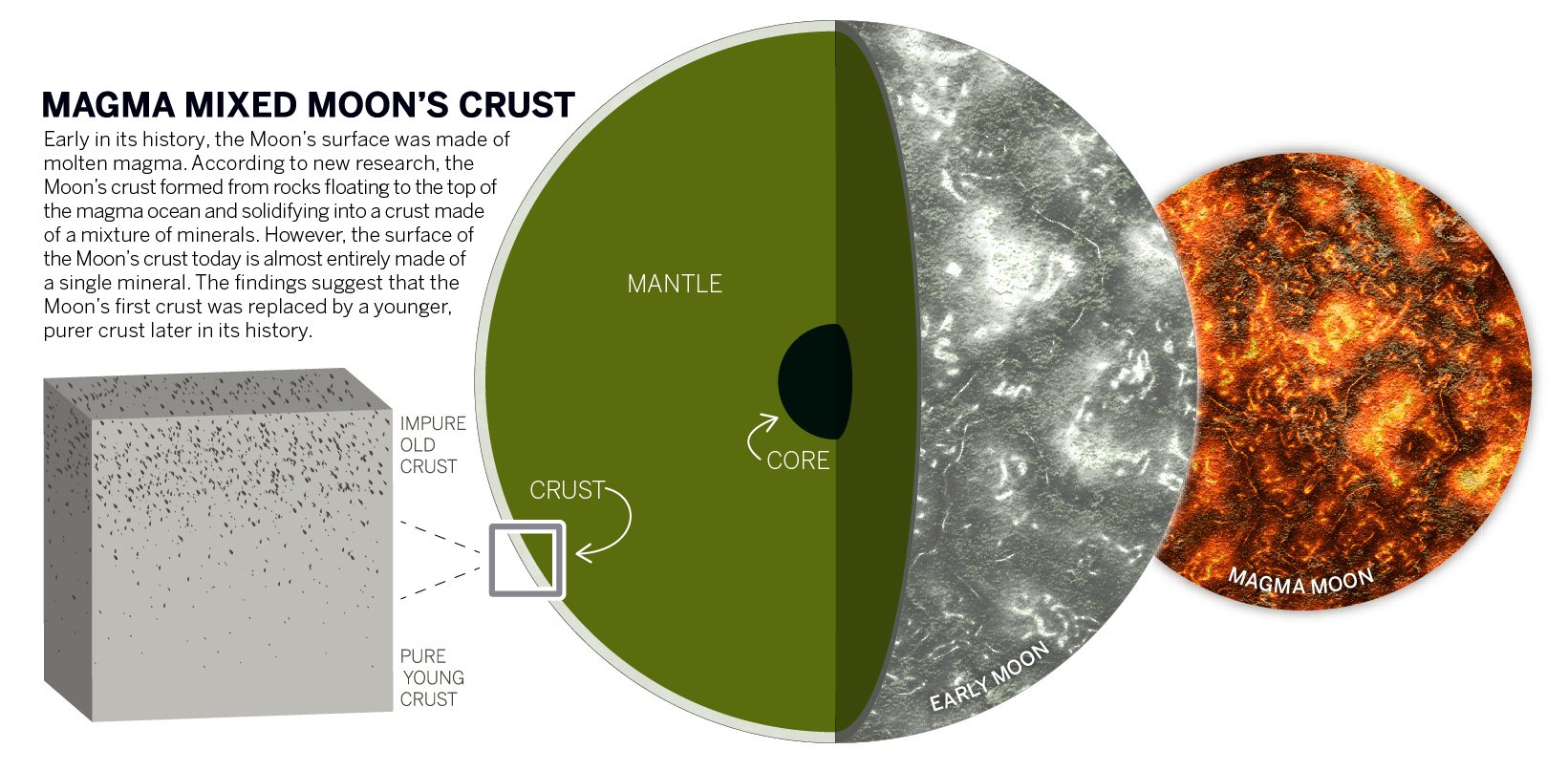

Formed due to a violent planetary collision between a Mars-sized object and the proto-Earth, the Moon spent its early years covered by a roiling global ocean of molten magma before cooling and forming the surface we see today.

A research team led by the University of Texas at Austin Jackson School of Geosciences recreated the early molten Moon in a laboratory and uncovered new insights on how the modern moonscape came to be.

The Moon’s crust initially formed from rock floating to the surface of the magma ocean and cooling.

“It’s fascinating to me that there could be a body as big as the Moon that was completely molten,” said Nick Dygert, an assistant professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

“That we can run these simple experiments, in these tiny little capsules here on Earth and make first order predictions about how such a large body would have evolved is one of the really exciting things about mineral physics.”

The team also found that one of the great mysteries of the lunar body’s formation – how it could develop a crust composed largely of just one mineral – cannot be explained by the initial crust formation and must have been the result of some secondary event.

Most of the Moon’s crust (98 percent) is made up almost entirely of a single mineral – plagioclase and the lack of crustal diversity has long puzzled scientists. As we know, our planet Earth – from which the Moon originated – has a rich diversity of minerals.

See also:

Moon’s Interior May Contain Lots Of Water!

Our Moon Is A Planet – Scientists Say

More About Astronomy

The prevailing model argues that the purity is due to plagioclase floating to the surface of the magma ocean over hundreds of millions of years and hardening into the Moon’s crust. Researchers tested this model by measuring the viscosity of lunar magma directly and then measured the time it took for a melt-resistant sphere to sink through the magma.

The results revealed that with a low viscosity or thickness, plagioclase would have floated to the top of the magma and in the process, it would have trapped other minerals, producing a crust that would not be pure plagioclase.

Satellite-based data says that a larger portion of the crust on the lunar surface is pure; it would mean that due to a second resurfacing on the Moon, the old mixed crust was replaced with younger, purer and hot layer plagioclase (a process known as “crustal overturn”).

Another possibility is that the older crust could have also been eroded away by asteroids slamming into the Moon’s surface.

The results were published in Geophysical Research Letters.

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts