Under The Hoods: The Brotherhoods And Sisterhoods Of Spain’s Holy Week

– “Spain is different!”. Napoleon took this view after his defeat by Spanish guerrilla warfare tactics. Generalissimo Franco’s government later made use of this slogan to promote Spain’s unique appeal to international tourists. The success of this tourism campaign is evident today: in 2016 Spain welcomed 75m tourists. Once an isolated peninsula on the edge of the European continent, Spain now ranks as the third most visited country in the world.

Foreign visitors spent €77 billion last year enjoying the country’s climate, food and cultural attractions. And one of the big ones is Easter – when Spain highlights a different approach to religious celebrations with colourful and macabre street processions.

The Spanish turn the streets into an improvised stage to dramatise Christ’s death and resurrection during Holy Week. Striking pictures of medieval figures in candlelit processions are published daily around the world. These pictures emphasise Spain’s distinctive identity. Parish groups, cofradías (fraternities), spend months on charity work and fundraising to stage the elaborate processions.

The parade of the Christ and the Virgin Mary statues circle through the community to celebrate the celestial glory of these figures that glide majestically above the crowds. On Spanish streets, everyone takes part in the drama – a moving chorus that brings together the musicians, players, bands and strolling audience.

What interests me is the social affiliation of these traditional groups; the bands of brothers. My research into identity reveals the psychological power of belonging to social groups. What is a celebration without the people? Local town halls stop traffic to enjoy each cofradías’s procession. In Seville, 60 parish groups take part in processions and published maps schedule the float departure times and street crossings.

The sumptuous floats with their sculptures of religious figures are followed by penitent sinners in monastic robes and pointed conical hoods that reach upwards for divine grace. Medieval hoods concealed the face and identity under the hood. In this way, individuals seeking repentance in public could remain anonymous. Across Spain’s diverse regions these processions bring the social community together. In Easter week, even the capital Madrid stops for the communal plays.

The brotherhoods demonstrate that collaboration, training and disciplined team work achieve remarkable performances. The fraternities display exceptional group cohesion that aligns with research analysis of the critical elements of super teams. First, the brotherhoods come together in their dedication to the rituals of Holy Week, Semana Santa – and they share a compelling purpose. Some members have waited 15 years to attain the revered honour of carrying the processional float.

The participants are skillful team members who adjust to each other’s strength, stamina and pace – this takes preparation and rigorous practice to build group cohesion. Members train together persistently for hours carrying concrete blocks to simulate the strain of carrying such heavy weights. Musicians and drummers put in hours of rehearsal to be able to march in step. A team leader directs a strict regimental formation to ensure a dignified progress. The choreography of a procession is a difficult balance for members manoeuvring through the cobbled streets alongside the eager crowds.

Over the centuries, the brotherhoods have had to change. Some groups date from the 14th century yet gradually over the past 30 years have widened participation to include women who now represent 40% of the membership. New groups have started up and women, celebrities, and children have joined the ranks.

These processions demonstrate a profoundly social sense of identity. Passion plays inspire a shared emotional response of applause, sentimental cries, prayers and chants. The processions are rooted in biblical stories, spiritual hopes and imaginary force. Despite the solemnity of the religious spectacle, the Spanish enjoy these fantastical rituals with great exuberance. In Jerez de la Frontera, I was amused to watch penitents remove their tall purple hoods to light a cigarette, check their mobile phones, or sip a glass of wine. Meanwhile, children devoured sweet marzipan versions of miniature penitents.

Spain is proud of these cultural traditions. The drama is alive, in motion and passionate, bringing together into a choral spectacle the bands, the penitents and the audience. The street is an improvised contemporary stage that knits together individual participants as a collective social group.

After Franco’s death in 1975, Spain shifted at remarkable speed from an authoritarian dictatorship to a democracy. This political transition was achieved through an agreement to forget the wrongs on both sides. The writer Giles Tremlett in his book The Ghosts of Spain reflects:

Similarly, the personal stories of group members are veiled as they cast long shadows processing through the night. To a curious observer, the sight of a white-cloaked spectre is ambivalent – a visual reference to Spain’s dark past. Ghosts of the Spanish Inquisition, ghosts of the Jews expelled from Al Andalus, and ghosts of the Civil War.

But at Easter these troublesome layers of past divisions and contradictions are temporarily hidden – shrouded under the social sharing of celebration. A social affirmation of identity rooted in a deep cultural heritage. The Spanish way to mark Easter is social – through collective participation that bolsters a sense of self. Yes, Spain is a part of the European community – and still proud to be different.

Creators of mankind

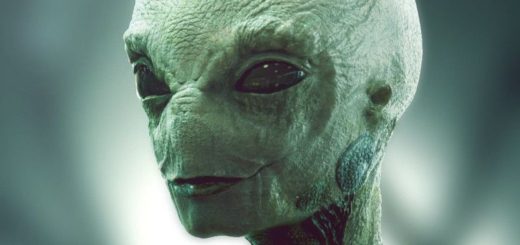

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts