UCR Astronomers Have Identified 121 Giant Planets That May Harbor Life

More than 100 giant planets that potentially host moons capable of supporting life, have been identifiedby researchers at the University of California, Riverside and the University of Southern Queensland.

The research will guide the design of future telescopes that can detect these potential moons and look for tell-tale signs of life, called biosignatures, in their atmospheres.

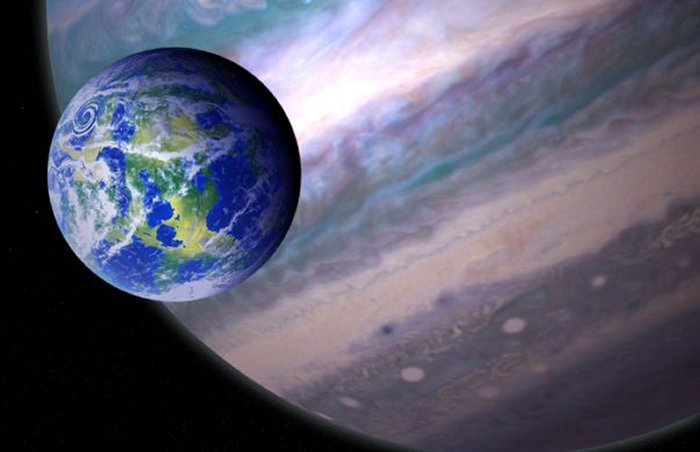

An artist’s illustration of a potentially habitable exomoon orbiting a giant planet in a distant solar system. NASA GSFC: Jay Friedlander and Britt Griswold

Since the 2009 launch of NASA’s Kepler telescope, have been identified thousands of planets outside our solar system, which are called exoplanets. A primary goal of the Kepler mission is to identify planets that are in the habitable zones of their stars, meaning it’s neither too hot nor too cold for liquid water — and potentially life — to exist.

Terrestrial (rocky) planets are prime targets in the quest to find life because some of them might be geologically and atmospherically similar to Earth. Another candidates that could sustain life are exomoons. Jupiter-like planets in the habitable zone may have such exomoons, which are worthy to observe and study.

“There are currently 175 known moons orbiting the eight planets in our solar system. While most of these moons orbit Saturn and Jupiter, which are outside the Sun’s habitable zone, that may not be the case in other solar systems,” said Stephen Kane, an associate professor of planetary astrophysics and a member of the UCR’s Alternative Earths Astrobiology Center.

“Including rocky exomoons in our search for life in space will greatly expand the places we can look.”

The researchers identified 121 giant planets that have orbits within the habitable zones of their stars. At more than three times the radii of the Earth, these gaseous planets are less common than terrestrial planets, but each is expected to host several large moons.

“Now that we have created a database of the known giant planets in the habitable zone of their star, observations of the best candidates for hosting potential exomoons will be made to help refine the expected exomoon properties,” said Michelle Hill, an undergraduate student at the University of Southern Queensland.

“Our follow-up studies will help inform future telescope design so that we can detect these moons, study their properties, and look for signs of life.”

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts