Supernova explosions may have helped shape Earth’s climate history

Star explosions may have played a greater role in Earth’s climate history than scientists thought.

Nearby supernovas have left a series of possible fingerprints in the tree-ring record here on Earth over the past 40,000 years, potentially disrupting our planet’s climate multiple times over this span, a new study reports.

“These are extreme events, and their potential effects seem to match tree-ring records,” study author Robert Brakenridge, a senior research associate at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado Boulder, said in a statement.

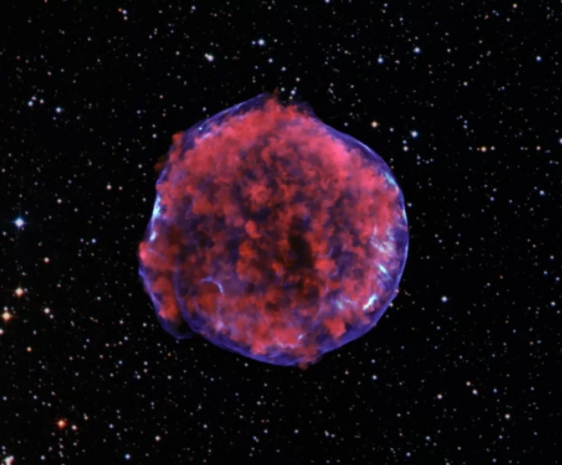

Brakenridge compiled a list of 18 supernovas — violent explosions that mark the deaths of certain kinds of stars — that occurred within about 4,900 light-years of Earth. He then compared the estimated timing of these cosmic events with spikes in carbon-14, as observed in the tree-ring record.

Carbon-14 is a radioactive isotope of carbon that contains eight neutrons in its atomic nucleus instead of the usual six. Carbon-14 is rare on Earth, and it doesn’t occur here naturally without some outside influence — namely, high-energy radiation streaming in from deep space, which can convert some of the “normal” carbon in our atmosphere to carbon-14 (which explains why this isotope is also known as radiocarbon).

“There’s generally a steady amount year after year,” Brakenridge said. “Trees pick up carbon dioxide, and some of that carbon will be radiocarbon.”

The amount of radiocarbon is not always steady, however. Scientists have spotted spikes in the tree-ring record, which have generally been attributed to powerful flares from our own sun. But Brakenridge suspected that supernovas could be involved, so he investigated a possible link.

And he found a tantalizing but tentative one: Eight of the closest supernovas on his list occurred around the same time as a brief radiocarbon spike. The association was especially strong for four supernovas, including one 13,000 years ago that ended the life of a star in the Vela constellation about 815 light-years from Earth.

Shortly after that explosion, radiocarbon levels shot up briefly by about 3% in Earth’s atmosphere, Brakenridge found.

The results are not conclusive, given the various uncertainties involved. For example, it’s difficult to date supernovas precisely; the inferred timing of the Vela explosion may be off by as much as 1,500 years, Brakenridge said. But he thinks that the new results, which were published online last week in the International Journal of Astrobiology, show that more research into a supernova-radiocarbon link is warranted.

“What keeps me going is when I look at the terrestrial record and I say, ‘My God, the predicted and modeled effects do appear to be there,” Brakenridge said.

He’s not the only scientist to suggest that supernovas may have significantly affected life on Earth. Other studies have postulated that nearby star explosions have caused or contributed to some mass extinctions, by altering our planet’s atmosphere and causing climatic shifts.

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts