Our Milky Way galaxy may be teeming with ocean worlds

Far-off alien planets covered in vast oceans might be common in our Milky Way galaxy, scientists find.

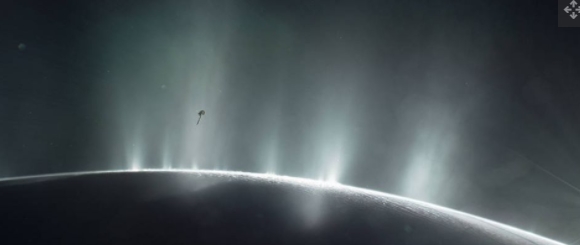

“Ocean worlds” are terrestrial planets that have significant amounts of water either on their surfaces or in a subsurface sea. Right here in our own solar system, Saturn and Jupiter host moons that fall under this watery category. For example, Enceladus, Saturn’s geyser-spewing moon, has a massive, global ocean made up of liquid saltwater that lies just below its icy surface. But how common are these “ocean worlds” throughout the cosmos?

In a new study, researchers decided to see how many planets in the Milky Way might fit into the category of “ocean world.” They also wanted to explore how many of these worlds might even spit watery plumes, stemming from their oceans, out into space as Enceladus does. And they found that more than a quarter of the 53 exoplanets they studied could potentially be ocean worlds.

“Plumes of water erupt from Europa and Enceladus, so we can tell that these bodies have subsurface oceans beneath their ice shells, and they have energy that drives the plumes, which are two requirements for life as we know it,” Lynnae Quick, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who specializes in volcanism and ocean worlds, said in a NASA statement. (Europa is one of Jupiter’s many moons.)

“So if we’re thinking about these places as being possibly habitable, maybe bigger versions of them in other planetary systems are habitable too,” Quick said.

To figure out how many of these ocean worlds might be lurking out there in the Milky Way, the scientists looked at 53 exoplanets that are a similar size to Earth, including the seven planets of the nearby TRAPPIST-1 system. They analyzed variables including exoplanet size, density, orbit, surface temperature, mass and distance from their star.

In addition to estimating that about a quarter of these planets could be ocean worlds, the team also found that most of them could have subsurface oceans under layers of ice. Additionally, the team found that many of these possible ocean worlds could be releasing even more energy than Enceladus and Europa do.

Now, “assumptions that go into these mathematical models are educated guesses,” the NASA statement reads. However, this information could be important in helping researchers to better choose which exoplanets they might want to study or where they might send probes in the future.

In the future, scientists could also test Quick’s findings by measuring the heat emitted by these worlds or by identifying any volcanic (or cryovolcanic, which includes liquid or vapor emissions instead of molten rock) eruptions. These could be identified in the light (and the wavelengths of that light) filtered out by a planet’s atmosphere.

These exoplanets are too far away to currently see in detail, especially because such details are often obscured by the light of a planet’s star. However, with future missions including NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, which is set to launch sometime in 2021, researchers could more closely investigate these worlds.

“Future missions to look for signs of life beyond the solar system are focused on planets like ours that have a global biosphere that’s so abundant it’s changing the chemistry of the whole atmosphere,” Aki Roberge, a NASA Goddard astrophysicist who collaborated with Quick on this analysis, added in the same statement. “But in the solar system, icy moons with oceans, which are far from the heat of the sun, still have shown that they have the features we think are required for life.”

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts