Hungry ‘Hot DOG’ Eats Nearby Galaxies, Fattens Its Black Hole

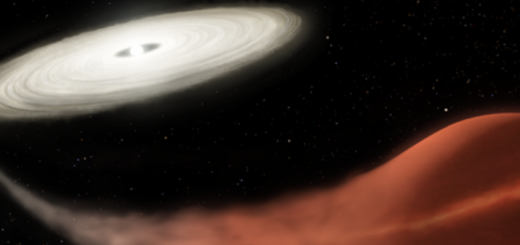

An artist’s impression of W2246-0526, the most luminous galaxy ever discovered and one with an incredibly hearty appetite. (NRAO/AUI/NSF) S. DAGNELLO

Galaxies in the farthest-most reaches of our universe are the epitome of extreme. Take W2246-0526. It may be smaller than our galaxy, but it possesses a hyperactive supermassive black hole that’s 4 billion times the mass of our sun and generating a whole lot more energy than our entire galaxy. It’s located 12.4 billion light-years away, meaning it is one of the earliest galaxies observed.

So, what’s the secret behind W2246’s hyperactivity? Well, it’s sucking the life out of other nearby galaxies, according to astronomers who’ve been scrutinizing the galaxy’s neighborhood. They published their findings in Science on Nov. 15. Gas is streaming into the galaxy’s core via vast flows through intergalactic space, feeding the galaxy’s black hole and stealing the lifeblood of star formation from its neighbors.

W2246 holds the record as the most luminous galaxy known and was first detected by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) mission. During the earliest epochs after the Big Bang, very luminous galaxies containing active black holes in their cores were commonplace, creating what astronomers call “quasi-stellar objects,” or quasars. A few of these quasars are choked with hot gas and dust that obscures our view into the galaxy’s core but generates a lot of infrared radiation. These rare quasars are known as “hot dust-obscured galaxies,” or “hot DOGs,” and it has been a mystery as to where all of the obscuring material comes from.

But now, we know.

Using observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/Sub-millimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, the Karl G Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico and the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers have identified vast “bridges” of dust-rich material being siphoned from three small companion galaxies near W2246.

“We’re seeing the linked companions, which means their interactions are definitely moving gas around in the system,” says Andrew Blain, a professor and astronomer from the University of Leicester in the U.K. “The presence of dust in that gas indicates the gas has been through a previous generation of stars and is able to cool and make its way down towards the supermassive black hole (in W2246’s core).”

Blain, who collaborated with an international team of researchers, adds that this period of intense activity could continue for another 200 million years. There’s enough fuel streaming into W2246 to feed and obscure the monstrous black hole and provide enough leftovers to drive the galaxy’s star formation — at the expense of the increasingly anemic three companion galaxies.

This intergalactic thievery provides an important clue as to how the most extreme galaxies in the early universe thrived, but W2246 is an outlier; it’s unlikely that our galaxy ever experienced such a dramatic childhood.

“Our supermassive black hole certainly had to grow by accreting mass, perhaps in a similar way,” adds Blain. “However, indications are that our galaxy’s black hole is about a thousand times smaller than W2246’s, and so it was very unlikely to have had such a dramatic phase.

“The Milky Way is a relatively typical galaxy, whereas W2246 is ‘one in a hundred million’ in the WISE survey where it was found.”

Ultimately, astronomers believe that galaxies like W2246 live fast and die young. Should hot DOGs gather too much obscuring material around them, they will eject vast quantities of gas and dust back out into their galaxy, damping further star formation and pushing the galaxy into early retirement.

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts