Here’s Why UFOs May Be to Blame for Climate Change Denial. Seriously.

On June 24, 1947, private pilot Kenneth Arnold was flying near Mt. Rainier, Washington, when a flash of light caught his attention. He then saw nine objects in a “V” formation with “tail-less” shapes unlike any aircraft he had seen before.

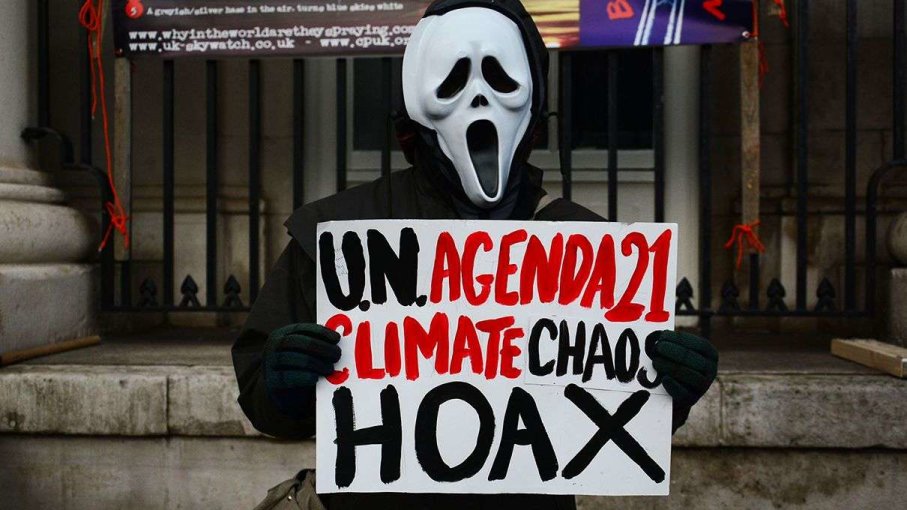

Although Arnold believed he had seen military aircraft conducting a test flight, the U.S. military insisted it had no such operations at the time. The flying objects Arnold thought he had seen, said U.S. Air Force officials, were nothing more than a mirage. The ensuing debate — over whether the U.S. government was withholding information from its citizens — launched not only conspiracy theories about UFOs, but contributed to generations of conspiracies involving everything from childhood vaccines to the terrorist attacks on 9/11.

Greg Eghigian, an associate professor of modern history at Pennsylvania State University, believes the sometimes-at-odds relationship between scientists and lay people can be traced back to the flying saucer era of the late 1940s, and he describes the roots of the skepticism in a December 2015 piece in the journal Public Understanding of Science.

“One of the things that marks the long history of this movement is the question of mistrust,” Eghigian says in a news release, “and I see this as part and parcel of some of the skepticism we see out there today … the UFO debate was kind of the granddaddy of them all and could be a model for looking at these other controversies.”

Scientists tend to believe that when the general public is either biased or uneducated, it largely doesn’t agree with scientific findings, Eghigian adds. However, it’s often less about a distrust of science than a distrust of scientific or governmental institutions.

“The politicization of science is driving this distrust now,” says Cassino, pointing to climate change and vaccine safety as two prime examples. “When scientific findings become a partisan issue, there are dramatic shifts in public perception.”

On the other hand, says political scientist Dan Cassino, the paranoia endemic to the Cold War era as the source of today’s distrust, rather than specifically to the UFO phenomenon.

“There was a bunch of stuff going on that the government wasn’t talking about. There were actual conspiracies going on,” says Cassino, associate professor of political science at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Madison, New Jersey. “But it was more the start of the Cold War that began the paranoid mindset. And it was more the Kennedy assassination in 1963 and Watergate in 1972 than UFOs that caused distrust of authority figures, including scientists.”

Robert Putnam, a political scientist and professor of public policy at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, reports the the number of Americans who trust the government in Washington, D.C., only “some of the time” or “almost never” has steadily risen from 30 percent in 1966 to 75 percent in 1992.

But that doesn’t mean conspiracy theories are going to be the new normal, as long as a few key adjustments are made in the collective discourse about science and scientific facts.

“What we need is a decoupling of science from partisanship,” Cassino says, “and a change in the way scientific findings are presented. If they are presented as controversy, there is tendency to not believe it as fact. If these findings are presented as fact, people tend to go along with it. The way science is presented in media matters.”

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts