Elusive Phoenicid Meteor Shower From Dead Comet Sighted Again After 58 Years

An elusive “Phoenicid meteor shower” (named after the constellation Phoenix located in the southern sky) has been detected by Japanese astronomers on December 5, 1956, during their voyage in the Indian Ocean.

Interestingly, it has not been observed again. Where did the Phoenicids come from and where did they go?

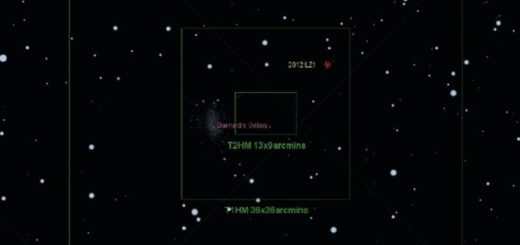

It is known about the Phoenicids that they are active from 29 November to 9 December, and their peak occurs around 5/6 December each year, and are best seen from the Southern Hemisphere. The Phoenicids appear to be associated with a stream of material from the disintegrating comet D/1819 W1 (or Comet Blanpain). This comet appeared in 1819 for the first time and then disappeared.

In 2003, astronomers discovered a minor body moving along the same orbit as Comet Blanpain had over 100 years ago and showed that it was the remains of Comet Blanpain.

The reason why Comet Blanpain reappeared as an asteroid was probably because all the gas and dust have escaped from this central body. Now rather than calling the object a “comet” it might be more accurate to refer to it as an “asteroid.” Although all of the gas and dust have escaped from Comet Blanpain into space, they now form a dust trail which revolves along almost the same orbit as Comet Blanpain itself, and gradually spread along the orbit. When such a dust trail encounters the Earth, the dust particles impinge into the atmosphere and ablate, which are observed as meteors.

Assuming that Comet Blanpain is the parent body of the Phoenicids, the teams performed calculations and predicted that the Phoenicids should be observed again on December 1, 2014.

The other team led by Mikiya Sato, an astronomical officer at Kawasaki Municipal Science Museum, and Junichi Watanabe, a professor of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan/SOKENDAI, made observations on the West Coast of Africa. Sato’s work was supported by additional data from NASA’s All Sky Fireball Network and radar observations at the University of Western Ontario, Canada – due to cloudy conditions.

Out of the 138 meteors observed at North Carolina, 29 were identified as Phoenicids. The Phoenicid activity peaked between 8 pm to 9 pm local time, very close to the predicted peak of the Phoenicid meteor shower, which was 7 pm to 8 pm. This fact has further supported that the observed meteors back-traced to the Phoenicid radiant are surely from Phoenicid meteor shower.

The data collected by the other sources also supported this result, but not everything matched the predictions. One discrepancy between the prediction and the observations was that the number of Phoenicids observed was only 10 percent of the prediction.

This indicates that Comet Blanpain was active, but only to a limited extent when the observed meteors were released from the comet when it approached the Sun in the early 20th Century. To summarize, the observed meteor shower is the first example for the astronomers where the evolution of a comet has been estimated.

Fujiwara enthusiastically states,“we would like to apply this technique to many other meteor showers for which the parent bodies are currently without clear cometary activities, in order to investigate the evolution of minor bodies in the Solar System.”

Fujiwara’s research is being published in the “Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan,” and Sato’s research will appear in the journal “Planetary and Space Science” very soon.

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts