5,000 year-old stone balls continue to baffle archaeologists

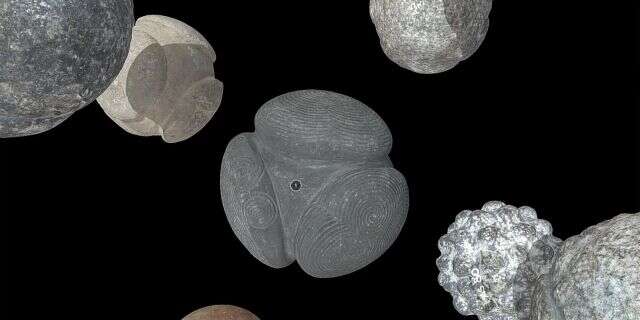

Some of the most enigmatic human-made objects from Europe’s late Stone Age — intricately carved balls of stone, each about the size of a baseball — continue to baffle archaeologists more than 200 years after they were first discovered.

More than 500 of the enigmatic objects have now been found, most of them in northeast Scotland, but also in the Orkney Islands, England, Ireland and one in Norway.

Archaeologists still don’t know the original purpose or meaning of the Neolithic stone balls, which are recognized as some of the finest examples of Neolithic art found anywhere in the world. But now, they’ve created virtual 3D models of the gorgeous balls, primarily to share with the public. In addition, the models have revealed some new details, including once-hidden patterns in the carvings on the balls. [In Photos: Amazing Ruins of the Ancient World]

Hugo Anderson-Whymark, a curator at National Museums Scotland who created the online models, explained that many functions have been proposed for the stone balls over the years.

Such proposals have included the possibility that they were made as the stone heads for crushing weapons, or standardized weights for Neolithic traders, or rollers for the transport of the giant stones used in megalithic monuments.

One theory is that the knobs on many of the carved stone balls were wound with twine or sinew, which allowed them to be thrown like slings or South American bolas. Other theories describe the balls as objects of religious devotion or symbols of social status.

“Many of the ideas you have to take with a pinch of salt, while there are others that may be plausible,” Anderson-Whymark told Live Science. “What’s interesting is that people really get their imaginations captured by them — they still hold a lot of secrets.”

Neolithic mystery

The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh has the world’s largest collection of carved stone balls, including around 140 originals from Neolithic (New Stone Age) sites in Scotland and the Orkney Islands, and 60 casts of similar objects from other places.

Although only a few are now on display in Edinburgh, a total of 60 3D models of Neolithic carved stone ballsfrom the museum collection have now been posted online — so that anyone interested in ancient wonders, anywhere in the world, can examine them in detail and from any angle.

The online collection includes the most famous of these objects, the Towie ball, which was found near the village of Towie in northeast Scotland around 1860. The ball is carved with intertwined spiral patterns on three of its four lobes, and is recognized as one of the finest examples of Neolithic art ever found. [In Photos: The World’s Oldest Cave Art]

Some early archaeologists found it hard to believe that such intricate objects could have been carved with only stone tools, Anderson-Whymark said, and so they wrongly attributed them to the Picts, who lived in Scotland during the late Iron Age and early Medieval period, between 1800 and 1100 years ago.

But later archaeologists were able to date the carved stone balls to the much earlier Neolithic period of prehistory, about 5,000 years ago, when only stone tools were used, he said.

Many of the ornamental motifs used on the carved stone balls, including the detailed circles and spirals carved into the Towie ball, were also found in carvings at Neolithic passage tombs, which feature underground burial chambers at the end of long stone-lined passageways, such as the Newgrange tomb in Ireland.

The similarity of the designs could show that people in different regions during the Neolithic period in Europe shared common ideas, which indicated some forms of interaction between their communities, Anderson-Whymark said.

Ancient objects in 3D

The online 3D models were created with photogrammetry, which involves uniting detailed photographs of the surface textures and colors of the objects with precise data about their size and shape.

The photogrammetry process has revealed new information about some of the balls, by revealing underlying patterns of carved and chipped markings on some of them that otherwise could not be clearly seen, he said.

He thinks that the key to understanding the carved stone balls lies in their “regular” size, which was perfect for being held in the hand while they were chipped or pecked by harder stone tools.

Creating one of the carved stone balls must have been a lengthy process — several of them show signs that their design evolved as they were worked on, perhaps over many years or even across generations, he said.

While discussion and speculation about their purpose and meaning to the Neolithic people will continue, the stone balls are likely to retain much of their enduring mystery, Anderson-Whymark said.

“We might be able to get a little bit more of that story out in the future by more detailed analysis of these things,” he said, “but they’re always going to be slightly enigmatic.”

Creators of mankind

Creators of mankind Description of “Tall white aliens”

Description of “Tall white aliens” Where they came from?

Where they came from? About hostile civilizations

About hostile civilizations The war for the Earth

The war for the Earth “Tall white aliens” about eternal life

“Tall white aliens” about eternal life Video: “Nordic aliens”

Video: “Nordic aliens” Aliens

Aliens Alien encounters

Alien encounters The aliens base

The aliens base UFO

UFO Technology UFO

Technology UFO Underground civilization

Underground civilization Ancient alien artifacts

Ancient alien artifacts Military and UFO

Military and UFO Mysteries and hypotheses

Mysteries and hypotheses Scientific facts

Scientific facts